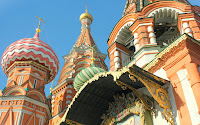

Legend has

it that Ivan had the architects blinded so that they could never build anything

comparable. This is a myth, however, as records show that they were employed a

quarter of a century later (and four years after Ivan’s death) to add an

additional chapel to the structure.

The Church

of St Vasily the Blessed, the northeastern chapel on the 1st floor, contains

the canopy-covered crypt of its namesake saint, one of the most revered in

Moscow. Vasily (Basil) the Blessed was known as a 'holy fool', sometimes going

naked and purposefully humiliating himself for the greater glory of God. He was

believed to be a seer and miracle maker, and even Ivan the Terrible revered and

feared him. This 10th chapel – the only one at ground level – was added in

1588, after the saint's death. Look for the icon depicting St Vasily himself,

with Red Square and the Kremlin in the background.

Novodevichy Convent

The

Novodevichy Convent was founded in 1524 to celebrate the taking of Smolensk from

Lithuania, an important step in Moscow’s conquest of the old Kyivan Rus lands.

The oldest and most dominant building on the grounds is the white Smolensk

Cathedral, with a sumptuous interior covered in 16th-century frescoes.

Novodevichy is a functioning monastery. Women are advised to cover their heads

and shoulders when entering the churches, while men should wear long pants.

From early

on, the ‘New Maidens’ Convent’ was a place for women from noble families to

retire – some more willingly than others. The convent’s most famous residents

included Irina Godunova (wife of Fyodor I and sister of Boris Godunov), Sofia

Alekseyevna (half-sister of Peter the Great), and Eudoxia Lopukhina (first wife

of Peter the Great).

Enter the

convent through the red-and-white Moscow-baroque Transfiguration Gate-Church (Преображенская

надвратная

церковь

), built

in the north wall between 1687 and 1689. All of these striking walls and

towers, along with many other buildings on the grounds, were rebuilt around

this time, under the direction of Sofia Alekseyevna. The elaborate bell tower (Колокольня

) against the east wall soars 72m

over the rest of the monastery. When it was built in 1690 it was one of the

tallest towers in Moscow (second only to the Ivan the Great Bell Tower in the

Kremlin).

The

centrepiece of the monastery is the white Smolensk Cathedral (Смоленский

собор

), built from 1524 to 1525 to house the precious Our Lady of Smolensk

icon. Previously surrounded by four smaller chapels, the floor plan was

modelled after the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin. The sumptuous interior

is covered in 16th-century frescoes, which are considered to be among the

finest in the city. The huge gilded iconostasis – donated by Sofia in 1685 –

includes icons that date from the time of Boris Godunov. The icons on the fifth

tier are attributed to 17th-century artists Simeon Ushakov and Fyodor Zubov.

The tombs of Sofia, a couple of her sisters, and Eudoxia Lopukhina are in the

south nave.

Sofia

Alekseyevna used the convent as a residence when she ruled Russia as regent in

the 1680s. During her rule, she rebuilt the convent to her liking – which was

fortunate, as she was later confined here when Peter the Great came of age.

After being implicated in the Streltsy rebellion, she was imprisoned here for

life, primarily inhabiting the Pond Tower (Напрудная башня). Sofia was later joined in her enforced retirement by Eudoxia

Lopukhina who stayed in the Chambers of Eudoxia Lopukhina (Лопухинские Палаты).

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

This

opulent and grandiose cathedral was completed in 1997 – just in time to

celebrate Moscow's 850th birthday. The cathedral’s sheer size and splendour

guarantee its role as a love-it-or-hate-it landmark. Considering Stalin's plan

for this site (a Palace of Soviets topped with a 100m statue of Lenin), Muscovites

should at least be grateful they can admire the shiny domes of a church instead

of the shiny dome of Ilyich’s head.

The

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour sits on the site of an earlier and similar

church of the same name, built in the 19th century to commemorate Russia’s

victory over Napoleon. The original was destroyed in 1931, during Stalin’s orgy

of explosive secularism. His plan to replace the church with a 315m-high Palace

of Soviets never got off the ground – literally. Instead, for 50 years the site

served another important purpose: the world’s largest swimming pool.

The

Cathedral replicates its predecessor in many ways. The central altar is

dedicated to the Nativity, while the two side altars are dedicated to Sts

Nicholas and Alexander Nevsky. Frescoes around the main gallery depict scenes

from the War of 1812, while marble plaques remember the participants.

The

original cathedral was built on a hill (since levelled). The contemporary

cathedral has been constructed on a wide base, which contains the smaller (but

no less stunning) Church of the Transfiguration. This ground-level chapel

contains the venerated icon Christ Not Painted by Hand, by Sorokin, which was

miraculously saved from the original cathedral.

Assumption Cathedral

On the

northern side of Sobornaya pl, with five golden helmet domes and four

semicircular gables, the Assumption Cathedral is the focal church of

pre-revolutionary Russia and the burial place of most of the heads of the

Russian Orthodox Church from the 1320s to 1700. A striking 1660s fresco of the

Virgin Mary faces Sobornaya pl, above the door once used for royal processions.

If you have limited time, come straight here. The visitors' entrance is at the

western end.

The

interior of the Assumption Cathedral is unusually bright and spacious, full of

warm reds, blues and gold. The west wall features a scene of the Apocalypse, a

favourite theme of the Russian Church in the Middle Ages. The pillars have

pictures of martyrs on them, as martyrs are considered to be the pillars of

faith. Above the southern gates are frescoes of Yelena and Constantine, who

brought Christianity to Greece and the south of Russia. The space above the

northern gate is taken by Olga and Vladimir, who brought Christianity to the

north.

Most of the

existing murals on the cathedral walls were painted on a gilt base in the

1640s, with the exception of three grouped together on the south wall: The

Apocalypse (Апокалипсис

),

The Life of Metropolitan Pyotr (Житие

Митрополита

Петра

) and All Creatures Rejoice in Thee

(О

Тебе

радуется

). These are attributed to Dionysius and his

followers, the cathedral's original 15th-century mural painters.

The tombs

of many of the leaders of the Russian Church (metropolitans up to 1590,

patriarchs from 1590 to 1700) are against the north, west and south walls. Near

the west wall is a shrine with holy relics of Patriarch Hermogen, who was

starved to death during the Time of Troubles in 1612.

Near the

south wall, the tent-roofed wooden throne is known as the Throne of Monomakh.

It was made in 1551 for Ivan the Terrible. Its carved scenes highlight the

career of 12th-century Grand Prince Vladimir Monomakh of Kiev – considered to

be Ivan's direct predecessor.

The

iconostasis dates from 1652, but its lowest level contains some older icons.

The 1340s Saviour with the Angry Eye (Спас

ярое

око

) is second from the right. On the

left of the central door is the Virgin of Vladimir (Владимирская

Богоматерь

), an early 15th-century Rublyov-school copy of

Russia's most revered image, the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God (Владимирская

Икона

Богоматери

).

The 12th-century original, now in Moscow's Tretyakov Gallery, stood in the

Assumption Cathedral from the 1480s to 1930. One of the oldest Russian icons,

the 12th-century red-clothed St George (Святой

Георгий

) from

Novgorod, is positioned by the north wall.

The

original icons of the lower, local tier are symbols of victory brought from

Vladimir, Smolensk, Veliky Ustyug and other places. The south door was brought

from the Nativity of the Virgin Cathedral in Suzdal.

Overlooking

the river, the Ascension Church, sometimes called the ‘white column’, is

Kolomenskoe Museum-Reserve's loveliest structure. Built between 1530 and 1532

for Grand Prince Vasily III, it probably celebrated the birth of his heir, Ivan

the Terrible. It was a revolutionary structure at the time, which experts

attribute to Italian masters.

As the

first brick church with a tent-shaped roof (previously found only on wooden

churches), it represents an important development in Russian architecture. This

break with the Byzantine tradition would pave the way for Moscow's great St

Basil’s Cathedral, which was built 25 years later. There is an exhibit on

milestones in Kolomenskoe history in the tent-roofed gatehouse near the church.

With its

two golden domes rising above the eastern side of Sobornaya pl, the Ivan the

Great Bell Tower is the Kremlin's tallest structure – a landmark visible from

30km away. Before the 20th century it was forbidden to build any higher in

Moscow. Purchase a ticket to the architectural exhibit inside for a

specifically timed admission to climb the 137 steps to the top for sweeping

views.

With its

two golden domes rising above the eastern side of Sobornaya pl, the Ivan the

Great Bell Tower is the Kremlin's tallest structure – a landmark visible from

30km away. Before the 20th century it was forbidden to build any higher in

Moscow. Purchase a ticket to the architectural exhibit inside for a

specifically timed admission to climb the 137 steps to the top for sweeping

views.

Ivan the

Great houses a multimedia presentation of the architectural history of the

Kremlin complex. Using architectural fragments and electronic projections, the

exhibit illustrates how the Kremlin has changed since the 12th century. Special

attention is given to individual churches within the complex, including several

churches that no longer exist. The 45-minute audio tour ends with a 137-step

climb to the top of the tall tower, yielding an amazing (and unique!) view of

Sobornaya pl, with the Church of Christ the Saviour and the Moskva-City

skyscrapers in the distance.

The bell

tower is only open when weather allows. Purchase your ticket (for a specific

admission time) at the ticket office in Alexander Garden before you enter the

Kremlin grounds. The number of people admitted for each time slot is extremely

limited, so it may require some flexibility.

The bell

tower's history dates back to the Church of Ioann Lestvichnik Under the Bells,

built on this site in 1329 by Ivan I. In 1505, the Italian Marco Bono designed

a new belfry, originally with only two octagonal tiers beneath a drum and a

dome. In 1600, Boris Godunov raised it to 81m. Local legend claims this was a

public works project designed to employ the thousands of people who had come to

Moscow during a famine, but historical documents contradict the story.

The

building's central section, with a gilded single dome and a 65-tonne bell,

dates from between 1532 and 1542. The tent-roofed annexe, next to the belfry,

was commissioned by Patriarch Filaret in 1642 and bears his name.

Archangel Cathedral

The

Archangel Cathedral at the southeastern corner of Sobornaya pl was for

centuries the coronation, wedding and burial church of tsars. It was built by

Ivan Kalita in 1333 to commemorate the end of the great famine, and dedicated

to Archangel Michael, guardian of the Moscow princes. It contains the tombs of

almost all of Muscovy's rulers from the 14th to the 17th century.

By the

early 16th century the Archangel Cathedral fell into disrepair and was rebuilt

between 1505 and 1508 by the Italian architect Alevisio Novi. Like the nearby

Assumption Cathedral, it has five domes and is essentially Byzantine-Russian in

style. However, the exterior has many Venetian Renaissance features, notably

the distinctive scallop-shell gables and porticoes.

By the

early 16th century the Archangel Cathedral fell into disrepair and was rebuilt

between 1505 and 1508 by the Italian architect Alevisio Novi. Like the nearby

Assumption Cathedral, it has five domes and is essentially Byzantine-Russian in

style. However, the exterior has many Venetian Renaissance features, notably

the distinctive scallop-shell gables and porticoes.

The tombs

of all Muscovy's rulers from the 1320s to the 1690s are here. The only absentee

is Boris Godunov, whose body was taken out of the grave on the order of a False

Dmitry and buried at Sergiev Posad in 1606. The bodies are buried underground,

beneath the 17th-century sarcophagi and 19th-century copper covers. Tsarevich

Dmitry, a son of Ivan the Terrible who died mysteriously in 1591, lies beneath

a painted stone canopy.

It was

Dmitry's death that sparked the appearance of a string of impersonators, known

as False Dmitrys, during the Time of Troubles. Ivan's own tomb is out of sight

behind the iconostasis, along with those of his other sons: Ivan (whom he

killed) and Fyodor (who succeeded him). From Peter the Great onwards, emperors

and empresses were buried in St Petersburg; the exception was Peter II, who

died in Moscow in 1730 and is here.

The

17th-century murals were uncovered during restorations in the 1950s. The south

wall depicts many of those buried here; on the pillars are some of their

predecessors, including Andrei Bogolyubsky, Prince Daniil and his father,

Alexander Nevsky.

Annunciation Cathedral

The

Annunciation Cathedral, at the southwest corner of Sobornaya pl, contains

impressive murals in the gallery and an archaeology exhibit in the basement.

The central chapel contains the celebrated icons of master painters Theophanes

the Greek and Andrei Rublyov.

The

Annunciation Cathedral, at the southwest corner of Sobornaya pl, contains

impressive murals in the gallery and an archaeology exhibit in the basement.

The central chapel contains the celebrated icons of master painters Theophanes

the Greek and Andrei Rublyov.

Many of the

murals in the gallery date from the 1560s. Among them are the Capture of

Jericho in the porch, Jonah and the Whale in the northern arm of the gallery,

and the Tree of Jesus on its ceiling. Other murals feature ancient philosophers

Aristotle, Plutarch, Plato, Socrates and others holding scrolls with their own

wise words.

The small

central part of the cathedral has a lovely jasper floor. The 16th-century

frescoes include Russian princes on the north pillar and Byzantine emperors on

the south, both with Apocalypse scenes above them.

But the

chapel's real treasure is the iconostasis, where restorers in the 1920s

uncovered early 15th-century icons by three of the greatest medieval Russian

artists. Theophanes likely painted the six icons at the right-hand end of the

deesis row, the biggest of the six tiers of the iconostasis. Andrei Rublyov is

reckoned to be the artist of most of the paintings at the left end of the

festival row – above the deesis row – while the seven at the right-hand end are

attributed to Prokhor of Gorodets.

The

basement – which remains from the previous 14th-century cathedral on this site

– contains a fascinating exhibit on the archaeology of the Kremlin. The

artefacts date from the 12th to 14th centuries, showing the growth of Moscow

during this period.

Donskoy

Monastery

Moscow's

youngest monastery, Donskoy was founded in 1591 as the home of the Virgin of

the Don icon, now in the Tretyakov Gallery. This icon is credited with the

victory in the 1380 battle of Kulikovo; it’s also said that, in 1591, the Tatar

Khan Giri retreated without a fight after the icon showered him with burning

arrows in a dream.

Most of the

monastery, surrounded by a brick wall with 12 towers, was built between 1684

and 1733 under Regent Sofia and Peter the Great. The Virgin of Tikhvin Church

over the north gate, built in 1713 and 1714, is one of the last examples of

Moscow baroque. In the centre of the grounds is the large brick New Cathedral,

built between 1684 and 1693. Just to its south is the smaller Old Cathedral,

dating from 1591 to 1593.

When

burials in central Moscow were banned after the 1771 plague, the Donskoy

Monastery became a graveyard for the nobility, and it is littered with

elaborate tombs and chapels.

Donskoy

Monastery is a five-minute walk from Shabolovskaya metro. Go south along ul

Shabolovka, then take the first street west, 1-y Donskoy proezd.

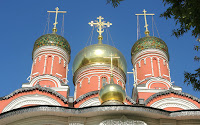

Church of

the Trinity in Nikitniki

Hidden

between big government blocks, this little gem of a church is an exquisite

example of Russian baroque. Built in the 1630s, its onion domes and tiers of

red-and-white spade gables rise from a square tower. Its interior is covered

with 1650s gospel frescoes by Simon Ushakov and others. A carved doorway leads

into St Nikita the Martyr’s Chapel, above the vault of the Nikitnikov merchant

family, who were among the patrons who financed the church's construction.

Church of

the Nativity of the Virgin in Putinki

When this

church was completed in 1652, Patriarch Nikon responded by banning tent roofs

like those featured here. Apparently, he considered such architecture too

Russian, too secular and too far removed from the Church’s Byzantine roots.

Fortunately, the Church of the Nativity has survived to grace this corner near

Pushkinskaya pl.

Novospassky

Monastery

Novospassky

Monastery, a 15th-century fort-monastery, is about 1km south of Taganskaya pl.

The centrepiece of the monastery, the Transfiguration Cathedral, was built by

the imperial Romanov family in the 1640s in imitation of the Kremlin’s

Assumption Cathedral. Frescoes depict the history of Christianity in Russia,

while the Romanov family tree, which goes as far back as the Viking Prince

Rurik, climbs one wall. The other church is the 1675 Intercession Church.

Novospassky

Monastery, a 15th-century fort-monastery, is about 1km south of Taganskaya pl.

The centrepiece of the monastery, the Transfiguration Cathedral, was built by

the imperial Romanov family in the 1640s in imitation of the Kremlin’s

Assumption Cathedral. Frescoes depict the history of Christianity in Russia,

while the Romanov family tree, which goes as far back as the Viking Prince

Rurik, climbs one wall. The other church is the 1675 Intercession Church.

Under the

riverbank, beneath one of the towers of the monastery, is the site of a mass

grave for thousands of Stalin’s victims. At the northern end of the monastery’s

grounds are the brick Assumption Cathedral and an extraordinary Moscow-baroque

gate tower.

Danilov

Monastery

The

headquarters of the Russian Orthodox Church stands behind white fortress walls.

On holy days this place seethes with worshippers murmuring prayers, lighting

candles and ladling holy water into jugs at the tiny chapel inside the gates.

The Danilov Monastery was built in the late 13th century by Daniil, the first

Prince of Moscow, as an outer city defence.

The

monastery was repeatedly altered over the next several hundred years, and

served as a factory and a detention centre during the Soviet period. It was

restored in time to replace Sergiev Posad as the Church’s spiritual and

administrative centre, and became the official residence of the Patriarch

during the Russian Orthodoxy’s millennium celebrations in 1988.

The

monastery was repeatedly altered over the next several hundred years, and

served as a factory and a detention centre during the Soviet period. It was

restored in time to replace Sergiev Posad as the Church’s spiritual and

administrative centre, and became the official residence of the Patriarch

during the Russian Orthodoxy’s millennium celebrations in 1988.

Enter

beneath the pink St Simeon Stylite Gate-Church on the north wall. The oldest

and busiest church is the Church of the Holy Fathers of the Seven Ecumenical

Councils, where worship is held continuously from 10am to 5pm daily. Founded in

the 17th century and rebuilt repeatedly, the church contains several chapels on

two floors: the main one upstairs is flanked by side chapels to St Daniil (on

the northern side) and Sts Boris and Gleb (south). On the ground level, the

small main chapel is dedicated to the Protecting Veil, and the northern one to

the prophet Daniil.

The yellow

neoclassical Trinity Cathedral, built in the 1830s, is an austere counterpart

to the other buildings. West of the cathedral are the patriarchate’s External

Affairs Department and, at the far end of the grounds, the Patriarch’s official

residence. Against the north wall, to the east of the residence, there’s a

13th-century Armenian carved-stone cross, or khachkar, a gift from the Armenian

Church. The church guesthouse, in the southern part of the monastery grounds,

has been turned into the elegant Danilovskaya Hotel.

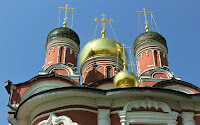

Church of

the Intercession at Fili

West of the

center, Fili is a residential neighbourhood that was once the estate of Lev

Naryshkin (brother-in-law to Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich and uncle to Peter the

Great). The story goes that Naryshkin’s brothers were killed in the Moscow

uprising of 1682. In their honour, he constructed this spectacular church. A

pink-brick wedding cake topped with gilded domes, it's an archetypal example of

the architectural style that came to be known as Naryshkin baroque.

From the

Fili metro station, walk two blocks north on Novozavodskaya ul.

Church of

St Nicholas in Khamovniki

This

church, commissioned by the weavers’ guild in 1676, is among the most colourful

in Moscow. The ornate green-and-orange-tapestry exterior houses an equally

exquisite interior, rich in frescoes and icons. Leo Tolstoy, who lived up the

street, was a parishioner at St Nicholas, which is featured in his novel

Resurrection. Look also for the old white stone house, built in 1689, which

housed the office of the weavers’ guild and textile shop (Бывшая

ткацкая

гильдия

; ul Lva

Tolstogo 10).

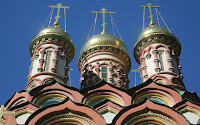

Monastery

of the Epiphany

This

monastery is the second-oldest in Moscow, founded in 1296 by Prince Daniil, son

of Alexander Nevsky. The current Epiphany Cathedral – with its tall, pink,

gold-domed cupola – was constructed in the 1690s in the Moscow baroque style.

If you're lucky, you may hear the bells ringing forth from the old wooden

belfry nearby.

The little

church occupying this site is a 1993 replica of the original 17th-century beauty, which was built in thanks for the 1612 expulsion of Polish invaders.

Kazan

Cathedral

The

original Kazan Cathedral was founded on this site at the northern end of Red

Square in 1636. For two centuries it housed the Virgin of Kazan icon, which

supposedly helped to rout the Poles. Three hundred years after it was built,

the cathedral was completely demolished, allegedly because it impeded the flow

of celebrating workers during holiday parades.

The

original Kazan Cathedral was founded on this site at the northern end of Red

Square in 1636. For two centuries it housed the Virgin of Kazan icon, which

supposedly helped to rout the Poles. Three hundred years after it was built,

the cathedral was completely demolished, allegedly because it impeded the flow

of celebrating workers during holiday parades.

Zaikonospassky

Monastery

This

monastery was founded by Boris Godunov in 1600, although the church was built

in 1660. The name means ‘Behind the Icon Stall’, a reference to the busy icon

trade that once took place here. The now-functioning, multitiered Saviour

Church is tucked into the courtyard away from the street.

On the

orders of Tsar Alexey, the Likhud brothers – scholars of Greek – opened the

Slavonic Greek and Latin Academy on the monastery premises in 1687. (Mikhail

Lomonosov was a student here.) The academy later became a divinity school and

was transferred to the Trinity Monastery of St Sergius in 1814.

Church of

the Grand Ascension

In 1831

poet Alexander Pushkin married artist Natalia Goncharova in the elegant Church

of the Grand Ascension, on the western side of pl Nikitskie Vorota. Six years

later he died in St Petersburg, defending her honour in a duel. Such passion,

such romance… The celebrated couple is featured in the Rotunda Fountain, erected

in 1999 to commemorate the poet’s 100th birthday.

In 1831

poet Alexander Pushkin married artist Natalia Goncharova in the elegant Church

of the Grand Ascension, on the western side of pl Nikitskie Vorota. Six years

later he died in St Petersburg, defending her honour in a duel. Such passion,

such romance… The celebrated couple is featured in the Rotunda Fountain, erected

in 1999 to commemorate the poet’s 100th birthday.

Down the

street, the festive Church of the Lesser Ascension sits on the corner of

Voznesensky per. Built in the early 17th century, it features whitewashed walls

and stone embellishments carved in a primitive style.

With its

two golden domes rising above the eastern side of Sobornaya pl, the Ivan the

Great Bell Tower is the Kremlin's tallest structure – a landmark visible from

30km away. Before the 20th century it was forbidden to build any higher in

Moscow. Purchase a ticket to the architectural exhibit inside for a

specifically timed admission to climb the 137 steps to the top for sweeping

views.

With its

two golden domes rising above the eastern side of Sobornaya pl, the Ivan the

Great Bell Tower is the Kremlin's tallest structure – a landmark visible from

30km away. Before the 20th century it was forbidden to build any higher in

Moscow. Purchase a ticket to the architectural exhibit inside for a

specifically timed admission to climb the 137 steps to the top for sweeping

views. By the

early 16th century the Archangel Cathedral fell into disrepair and was rebuilt

between 1505 and 1508 by the Italian architect Alevisio Novi. Like the nearby

Assumption Cathedral, it has five domes and is essentially Byzantine-Russian in

style. However, the exterior has many Venetian Renaissance features, notably

the distinctive scallop-shell gables and porticoes.

By the

early 16th century the Archangel Cathedral fell into disrepair and was rebuilt

between 1505 and 1508 by the Italian architect Alevisio Novi. Like the nearby

Assumption Cathedral, it has five domes and is essentially Byzantine-Russian in

style. However, the exterior has many Venetian Renaissance features, notably

the distinctive scallop-shell gables and porticoes. The

Annunciation Cathedral, at the southwest corner of Sobornaya pl, contains

impressive murals in the gallery and an archaeology exhibit in the basement.

The central chapel contains the celebrated icons of master painters Theophanes

the Greek and Andrei Rublyov.

The

Annunciation Cathedral, at the southwest corner of Sobornaya pl, contains

impressive murals in the gallery and an archaeology exhibit in the basement.

The central chapel contains the celebrated icons of master painters Theophanes

the Greek and Andrei Rublyov. Novospassky

Monastery, a 15th-century fort-monastery, is about 1km south of Taganskaya pl.

The centrepiece of the monastery, the Transfiguration Cathedral, was built by

the imperial Romanov family in the 1640s in imitation of the Kremlin’s

Assumption Cathedral. Frescoes depict the history of Christianity in Russia,

while the Romanov family tree, which goes as far back as the Viking Prince

Rurik, climbs one wall. The other church is the 1675 Intercession Church.

Novospassky

Monastery, a 15th-century fort-monastery, is about 1km south of Taganskaya pl.

The centrepiece of the monastery, the Transfiguration Cathedral, was built by

the imperial Romanov family in the 1640s in imitation of the Kremlin’s

Assumption Cathedral. Frescoes depict the history of Christianity in Russia,

while the Romanov family tree, which goes as far back as the Viking Prince

Rurik, climbs one wall. The other church is the 1675 Intercession Church. The

monastery was repeatedly altered over the next several hundred years, and

served as a factory and a detention centre during the Soviet period. It was

restored in time to replace Sergiev Posad as the Church’s spiritual and

administrative centre, and became the official residence of the Patriarch

during the Russian Orthodoxy’s millennium celebrations in 1988.

The

monastery was repeatedly altered over the next several hundred years, and

served as a factory and a detention centre during the Soviet period. It was

restored in time to replace Sergiev Posad as the Church’s spiritual and

administrative centre, and became the official residence of the Patriarch

during the Russian Orthodoxy’s millennium celebrations in 1988. The

original Kazan Cathedral was founded on this site at the northern end of Red

Square in 1636. For two centuries it housed the Virgin of Kazan icon, which

supposedly helped to rout the Poles. Three hundred years after it was built,

the cathedral was completely demolished, allegedly because it impeded the flow

of celebrating workers during holiday parades.

The

original Kazan Cathedral was founded on this site at the northern end of Red

Square in 1636. For two centuries it housed the Virgin of Kazan icon, which

supposedly helped to rout the Poles. Three hundred years after it was built,

the cathedral was completely demolished, allegedly because it impeded the flow

of celebrating workers during holiday parades. In 1831

poet Alexander Pushkin married artist Natalia Goncharova in the elegant Church

of the Grand Ascension, on the western side of pl Nikitskie Vorota. Six years

later he died in St Petersburg, defending her honour in a duel. Such passion,

such romance… The celebrated couple is featured in the Rotunda Fountain, erected

in 1999 to commemorate the poet’s 100th birthday.

In 1831

poet Alexander Pushkin married artist Natalia Goncharova in the elegant Church

of the Grand Ascension, on the western side of pl Nikitskie Vorota. Six years

later he died in St Petersburg, defending her honour in a duel. Such passion,

such romance… The celebrated couple is featured in the Rotunda Fountain, erected

in 1999 to commemorate the poet’s 100th birthday.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий